By Alice Doyel

Guest blogger

Lord of the Flies was written by Sir William Golding and published in 1954, for which he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1984. (1) What was the basis for the book? (2) How does it affect systemic racism? (3) How a 1965 true story contradicts Golding’s thesis.

Lord of the Flies was written by Sir William Golding and published in 1954, for which he won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1984. (1) What was the basis for the book? (2) How does it affect systemic racism? (3) How a 1965 true story contradicts Golding’s thesis.

(1) Golding’s personal life is the backstory of the novel. He’s an extremely complex man. In the lengthy biography by John Carey, he wrote: “Golding’s childhood as he describes it in his unpublished journals and memoirs could not be called happy. He was over-sensitive, timid, fearful, lonely, and imaginative to the point of hallucinations. He was alienated from his parents and his brother, and had no friends.”

(1) Golding’s personal life is the backstory of the novel. He’s an extremely complex man. In the lengthy biography by John Carey, he wrote: “Golding’s childhood as he describes it in his unpublished journals and memoirs could not be called happy. He was over-sensitive, timid, fearful, lonely, and imaginative to the point of hallucinations. He was alienated from his parents and his brother, and had no friends.”

Golding did not improve as he got older. He referred to himself as a “monster.” Golding, who was bullied, turned to bullying others. He lacked self-esteem, suffered from chronic depression, and was a life-long alcoholic. His adverse interactions with women were likely based on his mother’s extreme detachment from Golding throughout her life. Golding attempted to rape a 14-year-old girl when he was on break as a freshman at Oxford. He told the girl, as she fought him off and ran away, that he did not intend to hurt her. A Guardian article provides some insight into this event and other aspects of the man.

There is no scientific rationale for the violent actions of the youths portrayed in Lord of the Flies. One theory is that Golding wrote this dystopian novel in contradiction to utopian works about children living idyllic lives when marooned on a South Pacific Island. We can assume that Golding read the Mutiny on the Bounty trilogy, where the early years of the mutineers’ settlement on Pitcairn Island were fraught with violent disruptions. However, these mutineers were hardly schoolboys.

Lord of the Flies has little to do with reality. In the 1950s there was little understanding of the complex interactions of nature, nurture, and environment. How you were born was who you were.

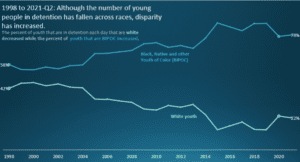

(2) Systemic Racism – If we falsely assume the nature of young males is harmful and violent, it is easy to take the next steps of preschool exclusions, school exclusions, and juvenile incarceration. Then we expand this base to include female students. If anyone has any doubts about the racial disparity in our school-to-prison pipeline, we only need to look at King County’s juvenile detentions statistics.

(2) Systemic Racism – If we falsely assume the nature of young males is harmful and violent, it is easy to take the next steps of preschool exclusions, school exclusions, and juvenile incarceration. Then we expand this base to include female students. If anyone has any doubts about the racial disparity in our school-to-prison pipeline, we only need to look at King County’s juvenile detentions statistics.

[King County includes Seattle, Bellevue, and over 50 other suburbs, towns, and rural communities.]

In 1998 BIPOC youth were 58% of those in detention.

As incarcerations were decreased, the percent of BIPOC youths incarcerated increased to 78%.

King County’s Zero Youth Detention director, Derrick Wheeler-Smith, states, “Look at the numbers of young people particularly black and brown young men – whose lives are derailed, uprooted and cut short by the legal system.”

(3) The True Story Contradicting Golding’s Thesis: Sources edited for length, clarity, and some conflicting information on minor details. The Guardian and an after-the-fact video documentary by Australian Public Broadcast Service (20 min, 07sec)

In 1965 six boys growing up in Tonga (Polynesia), ages 13 through 16, were bored “witless” at their strict Catholic boarding school. They decided to escape by secretly traveling 500 miles to Fiji by boat.

They stealthily “borrowed” a fisherman’s boat. The boys’ provisions were only two sacks of bananas, a few coconuts, and a small gas burner. It didn’t occur to any of them to bring a map, let alone a compass.

The small craft quietly left the harbor that evening. Skies were fair. The sea was calm. They fell asleep.

A few hours later they awoke in the dark to water crashing down over their heads. They hoisted the sail, which the wind promptly tore to shreds. Then the rudder broke. They drifted for eight days, without food or water. The boys tried catching fish. They managed to collect some rainwater in hollowed-out coconut shells and shared it equally between them, each taking a sip in the morning and in the evening.

On the eighth day, they spied a hulking mass of rock, jutting up more than a thousand feet out of the ocean. They landed the boat on this small island.

They survived initially on fish, coconuts, tame birds (they drank the blood as well as eating the meat); seabird eggs were sucked dry. Later, when they got to the top of the island, they found an ancient volcanic crater, where people had lived a century before. There the boys discovered wild taro, bananas, and chickens which had been reproducing for 100 years.

The boys agreed to work in teams of two, drawing up a strict roster for garden, kitchen, and guard duty. Sometimes they quarreled. Whenever that happened, they solved it by imposing a time-out. Their days began and ended with song and prayer. One of the boys fashioned a makeshift guitar from a piece of driftwood, half a coconut shell, and six steel wires salvaged from their wrecked boat and played it to help lift their spirits. And their spirits needed lifting. All summer long it hardly rained, driving the boys frantic with thirst. They tried constructing a raft in order to leave the island, but it fell apart in the crashing surf.

The boys agreed to work in teams of two, drawing up a strict roster for garden, kitchen, and guard duty. Sometimes they quarreled. Whenever that happened, they solved it by imposing a time-out. Their days began and ended with song and prayer. One of the boys fashioned a makeshift guitar from a piece of driftwood, half a coconut shell, and six steel wires salvaged from their wrecked boat and played it to help lift their spirits. And their spirits needed lifting. All summer long it hardly rained, driving the boys frantic with thirst. They tried constructing a raft in order to leave the island, but it fell apart in the crashing surf.

Worst of all, Stephen slipped one day, fell off a cliff, and broke his leg. The other boys picked their way down after him, and then helped him back up to the top. They set his leg using sticks and leaves. “Don’t worry,” one joked. “We’ll do your work, while you lie there like King Taufa‘ahau Tupou himself!”

Captain Warner, their rescuer wrote, “By the time we arrived [15 months later] the boys had set up a small commune with food garden, hollowed-out tree trunks to store rainwater, a gymnasium with curious weights, a badminton court, chicken pens, and a permanent fire, all from handiwork, an old knife blade, and much determination.”

When they returned home, the boys were charged with the theft of the boat. However, Captain Warner paid for the boat, saving the boys from prosecution.

“Lean On Me” Written and Sung by Bill Withers

“Lean On Me” Written and Sung by Bill Withers

(4min,17 sec) [See full lyrics below]

https://youtu.be/fOZ-MySzAac

Lean on me

When you’re not strong

And I’ll be your friend

I’ll help you carry on…

Growing up in the coal-mining town of Slab Fork, West Virginia, Bill Withers learned a lot about helping neighbors when they needed you. He missed that human connection when he moved to L.A., where childhood memories of togetherness provided the inspiration for “Lean On Me.”

Source: RollingStone

Next Blog Post: Learning True History: Personal Documents Written as Hitler Overtook Poland

Lyrics for “Lean On Me”

Sometimes in our lives

We all have pain

We all have sorrow

But if we are wise

We know that there’s always tomorrow

Lean on me

When you’re not strong

And I’ll be your friend

I’ll help you carry on…

For it won’t be long

Till I’m gonna need somebody to lean on

Please swallow your pride

If I have things you need to borrow

For no one can fill

Those of your needs that you won’t let show

You just call on me brother when you need a hand

We all need somebody to lean on

I just might have a problem that you’ll understand

We all need somebody to lean on

Lean on me

When you’re not strong

And I’ll be your friend

I’ll help you carry on…

For it won’t be long

Till I’m gonna need somebody to lean on

You just call on me brother

When you need a hand

We all need somebody to lean on

I just might have a problem that you’ll understand

We all need somebody to lean on

If there is a load you have to bear

That you can’t carry

I’m right up the road,

I’ll share your load

If you just call me

Call me

If you need a friend