By Alice Doyel

Guest blogger

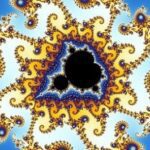

Benoit Mandelbrot brought us Fractal Geometry. It is the geometry of all forms of nature: mountains and shorelines, weather systems, the plant and animal worlds, inside our bodies, and each of our cells. Mandelbrot says, “I play with pictures, not formulas, and that is what I have done all my life.”

Benoit Mandelbrot brought us Fractal Geometry. It is the geometry of all forms of nature: mountains and shorelines, weather systems, the plant and animal worlds, inside our bodies, and each of our cells. Mandelbrot says, “I play with pictures, not formulas, and that is what I have done all my life.”

We have cell phones today, without outside antennae, that can use Wi-Fi, GPS, and Bluetooth simultaneously due to fractal technology. The wire’s pattern creates smaller and smaller duplicates of itself, fitting invisibly inside our phones. The future uses of fractal technology for understanding nature and innovating electronics, on earth and in space, are endless.

Mandelbrot created a simple geometric method to explain the infinitely complex. “Think not of what you see, but what it took to produce what you see.” Mandelbrot teaches that the whole looks similar to its parts, and that continues to each of its smaller parts. It’s a simple geometric concept that explains the chaotic, most complex, and dynamic structures on earth and in space. Fractals, The Hidden Dimension by PBS gives a very understandable 15-minute history of how fractal geometry developed, how we use them today, what it will do for our future.

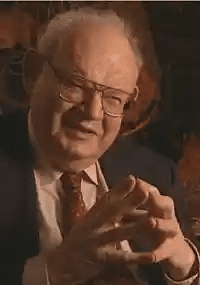

Mandelbrot looks at the world differently than most scientists. His childhood, youth, and education took numerous twists and turns that figure into his mental diversity. Listen to Mandelbrot speak about some of his family’s and his own complex history in this delightful 4-minute video. Here are just a few points of interest from the interview:

- The Mandelbrots were a Lithuanian Jewish family. Benoit’s great-grandfather was a very strong figure. As a young man, he walked to Petersburg, where he eventually became prime minister to the Emperor. When he returned many years later, he decided that his three granddaughters should all be doctors. Consequently, Mandelbrot’s mother studied to become a doctor. She and Benoit’s father married and had their first child.

- Benoit’s mother was a doctor throughout the terrible years of World War I, a civil war in a region of Russia where they were living, and the 1918 influenza pandemic. This pandemic caused the death of many children. Their young son died during the pandemic.

- Benoit was born after the pandemic was over, in 1924, in Warsaw. His mother feared losing Benoit, her second son, to an epidemic. She refused to send him to school.

- Instead, an uncle was his tutor, a man who knew nothing of teaching children. The alphabet and multiplication tables were ignored because the uncle did not think these were fun. Mandelbrot says he learned the beginning and end of the alphabet, but not the middle letters. He learned much of the multiplication table over time, but still had gaps in this knowledge. The uncle taught Benoit how to read maps, how to play chess, and how to argue and hold strong opinions on topics of his uncle’s interest.

- In Mandelbrot’s words, “It was quite strange, a strange way to begin an education.”

MacTech’s biography of Mandelbrot speaks further to his unusual education. “Mandelbrot’s family emigrated to France in 1936. Mandelbrot attended the Lycée Rolin in Paris up to the start of World War II, when his family moved to Tulle in central France. This was a time of extraordinary difficulty for Mandelbrot who feared for his life on many occasions. The war, the constant threat of poverty, and the need to survive kept him away from school and college” until after World War II.

“Mandelbrot now attributed much of his success to this unconventional education. It allowed him to think in ways that might be hard for someone who, through a conventional education, is strongly encouraged to think in standard ways. It also allowed him to develop a highly geometrical approach to mathematics, and his remarkable geometric intuition and vision began to give him unique insights into mathematical problems.”

“Mandelbrot now attributed much of his success to this unconventional education. It allowed him to think in ways that might be hard for someone who, through a conventional education, is strongly encouraged to think in standard ways. It also allowed him to develop a highly geometrical approach to mathematics, and his remarkable geometric intuition and vision began to give him unique insights into mathematical problems.”

How Does Help This Address Mathematical Education for Our School Children?

Stanford University’s Jo Boaler says teachers and parents should stop using math flashcards, stop drilling kids in addition and multiplication, and especially stop forcing students to do calculations quickly under time pressure.

“Drilling without understanding is harmful,” Boaler said. “I’m not saying that math facts aren’t important. I’m saying that math facts are best learned when we understand them and use them in different situations.”

She explains that the key to success in math is having something called “number sense,” and number sense is developed through “rich” mathematical problems. Too much emphasis on rote memorization, she says, inhibits students’ abilities to think about numbers creatively, to build them up, and break them down. She cites her own study, which found that low-achieving students tended to memorize methods and were unable to interact with numbers flexibly.

“Some students are fine with [rote memorization quizzes],” she said. “But when we combine those who are stressed with those who have turned away from math because of them, we have a large section of the U.S. population that goes across all achievement levels.”

A Final Thought, Sent in by Tara Vasanth, Our Artist for This Diversity Series:

“Great minds think differently. That is what makes them great minds. The world has not progressed as it has because everyone thought the same way, and was complacent in their thoughts. Curiosity drives innovation and progress. But if we can’t listen to these new innovative ideas because we are so used to thinking in the same way, we will never progress.” Grace Wong, Huffpost Contributor

Next Blog Post: Middle School – Pipeline to Prison or Pathway to Brilliance?

Joyful Activity for Those Who Like Baking: Mandelbrot, A Jewish Cookie.

It is a cousin to the Italian Biscotti, made with almonds and twice baked. Unlike biscotti, it is soft on the inside. It was a treat during my childhood, especially when fresh-baked from the oven or bakery.

It is a cousin to the Italian Biscotti, made with almonds and twice baked. Unlike biscotti, it is soft on the inside. It was a treat during my childhood, especially when fresh-baked from the oven or bakery.

Click here for the recipe.