By Alice Doyel

Guest blogger

Suicide is the Second Leading Cause of Death from Ages 10 to 24 Years.

Part 2 of Personal Stories

Written by People with Bipolar II, Each of Whom We Nearly Lost to Suicide,

Each Whose Suicidal Thoughts and Ideation Began in Their Youth.

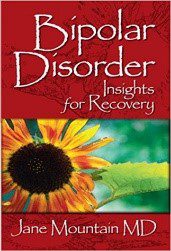

Today’s story is by Jane Mountain.

I was five years old when I walked up and down the block crying. At that early age, I knew something was wrong with me, and I wondered what it was. In the early grades, I asked myself constantly why kids didn’t like me. I remember saying to myself, “I like me; why don’t they?” Kids would tease me, saying, “Jane the Brain,” and I felt hurt but didn’t know how to stop them. I didn’t want to be reduced to just being a brain rather than a whole person.

I was five years old when I walked up and down the block crying. At that early age, I knew something was wrong with me, and I wondered what it was. In the early grades, I asked myself constantly why kids didn’t like me. I remember saying to myself, “I like me; why don’t they?” Kids would tease me, saying, “Jane the Brain,” and I felt hurt but didn’t know how to stop them. I didn’t want to be reduced to just being a brain rather than a whole person.

I think it is very important for adults to understand that bipolar disorder can strike at a very young age and that it often goes unnoticed. In my case, I felt the internal suffering of depression, but no one else seemed to notice. Often others don’t realize how much a person with bipolar depression is suffering because we are viewed as capable and gifted.

Later, when I was middle school age, I experienced a lengthy depression. I believe it affected my work at school even though I continued to get top grades. I felt bored at school for the first time, and this boredom caused me to question why I was not enjoying school as I always had before. Today I know this boredom was caused by an inability to feel pleasure due to depression. It’s important to understand that many kids with depression or bipolar depression are trying to make sense of their moods. And their depressive symptoms are not always like those of adults.

By the time I was in high school, I began to have suicidal thoughts. I convinced myself that was normal as long as they didn’t occur more than once a day. Suicidal thoughts are not normal, and they need to be addressed. I used once a day thinking, both to deny there was anything wrong and to give myself a bit of control. I could stave off thoughts of suicide by not allowing them to happen more than once a day. Later in life, I was unable to stop suicidal thoughts, and they became automatic, painful, and difficult to deal with, even though I was in treatment.

When I was in high school, one of my teachers discouraged me from becoming a doctor, saying I was too painfully shy to do so. I changed my career plans but later accomplished them. As an adult, I look back at my teacher’s advice and wish he had offered to help me learn social skills instead of making them a roadblock. When kids experience bipolar depression, their development is often uneven. They can be far ahead of normal developmental milestones in some areas and behind in others. They may excel in some areas, as I did in academics, but struggle in other areas such as developing social skills.

As an adult, I overcame my suicidal thoughts through treatment and through wellness skills that taught me to stop the loop of suicidal thinking that came unbidden to my brain. I stopped the loop, first by saying again and again, “NO, I refuse these thoughts!” and then over time, I found more ways to deal with suicidal thinking. Today I am free of this kind of thinking. Even though I never attempted suicide, suicidal thinking brings added pain to the suffering of depression. Many people with bipolar depression struggle with such thinking even though they never make attempts to harm themselves.

Jane’s adult years exhibit her Super Powers of recreating herself several times: Professional Violinist in Los Angeles orchestras (California State University); Family Medicine Physician (University of South Dakota School of Medicine); Author of Books on Bipolar Disorder; Founder/Leader of Depression/Bipolar Recovery Group of Midtown Denver; Pastor, Harbor of Grace Lutheran Church (Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg).

Jane’s adult years exhibit her Super Powers of recreating herself several times: Professional Violinist in Los Angeles orchestras (California State University); Family Medicine Physician (University of South Dakota School of Medicine); Author of Books on Bipolar Disorder; Founder/Leader of Depression/Bipolar Recovery Group of Midtown Denver; Pastor, Harbor of Grace Lutheran Church (Lutheran Theological Seminary at Gettysburg).

Students with suicidal thoughts need people whom they can trust to talk to about their feelings and fears. Students should not be made to feel guilty nor weak nor self-blaming. They need a listener with empathy, who can give them understanding, support, and guidance. They need a person who can get them to timely resources to save their lives. National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 800-273-8255

Super Resource: QPR Institute – Question. Persuade. Refer. Providing online training that enables anybody to learn how to prevent suicide.

Next Blog Post: The Mind Diversity of Autism, Part 1

Special Blog Bonus: “The Black Bird That Dogs Me – Experiencing a Different Brain” By Jane Mountain

Churchill described living with depression as having a black dog that followed him wherever he went. I think of my illness as the black bird that dogs me.

Churchill described living with depression as having a black dog that followed him wherever he went. I think of my illness as the black bird that dogs me.

When I walk in the park, I feel especially blessed when I see my favorite bird, the Cormorant, on the lake. On a good day, I am like this black bird, floating deep in the water, dipping my whole being into the waters of life. But the Cormorant is unlike the geese and ducks that inhabit the same lake; it does not float upon the water but rather in it. That is how I yearn to be, so much a part of life that I am nearly sinking into its essence.

The Cormorant appeals because of its differences from other waterfowl — it “lacks.” This black bird lacks the water-repellent oils that keep the other birds afloat above the water, causing it to sink nearly to its shoulders. Its long neck shows above the surface as if proud of its failure to be overcome by the water’s drowning edge! This lack is its gift.

I also have a lack that leaves me sinking deeply into life — a lack of brain chemistry that causes my depressions. On a good day, this lack leaves me floating deeply and experiencing life with a different vantage. I can look far above the water but at the same time I am engulfed by life. On a good day.

The Cormorant dives, head first, sinking low in search of fish. Its unoiled wings and sleek build allow it to disappear for minutes. When will it return and what the prize, if any?

I too will dive and sink — the world surrounding me, and I lacking buoyancy. How deep the depression? Like the Cormorant, no one knows where I shall again appear.

After spreading its oil-less wings to dry, the Cormorant flies, goose-like but silent. Like the Cormorant, I too fly silently — unaware of the eyes that watch me.

The Cormorant is the black bird that dogs me. I cannot escape the dogging, for my illnesses is always with me. I fly noiselessly and I sink into the depths, returning with what, I do not know. I float surrounded, unprotected from life, with shoulders, neck, and head lending a brave perspective.

I watch my favorite bird that dogs me, hating the lack in brain chemistry that makes me so different — so lacking compared to others, yet at times sharing the heights and depths I obtain that force me to spread my wings toward worlds of enrichment.

I watch my favorite bird that dogs me, hating the lack in brain chemistry that makes me so different — so lacking compared to others, yet at times sharing the heights and depths I obtain that force me to spread my wings toward worlds of enrichment.